In 1989 I joined a company that had just launched a new computer system to manage travel bookings.

In 2013 I left the company. And the same computer system was still handling travel bookings.

24 years.

Obviously in IT, as in many other things, but more so in IT, 24 years is an eternity.

How is it possible for a system to survive all the technological advances of 24 years?

Computers had nothing to do with it. New operating systems had nothing to do with it. New programming languages had nothing to do with it.

But, above all, the business had also changed a lot.

Until 1989, the previous system was based on managing reservations on big boards in call centres.

And the system was a revolution in that it made it possible to check availability and prices and to confirm bookings from a computer terminal.

One of those terminals with a green screen and a massive keyboard that required you to memorise key combinations and commands for each operation.

In 2013, all travel bookings were made automatically through the website to which agencies all over Spain had access.

But, in addition, the vast majority of bookings were made automatically from the interconnected systems of different travel agencies and other providers.

And many bookings required online checking of availability and prices of services that were in other suppliers’ systems.

How is it possible that a system, designed as a self-contained thing, with its own screens and database, could evolve into a system that was interconnected with suppliers and customers and accessible through websites?

Well, that was partly our job: to surround the system with mechanisms that allowed it to evolve and connect with others as technology advanced.

But the really important question is: How is it possible that this system was not eliminated and replaced by others with more current technologies?

Because with new technologies it would surely be easier to make interconnections with other systems or develop websites to access the system or any other functionality that would have appeared after the launch of these obsolete technologies.

If we ask those who originally created that system, they would tell us that it was very well done.

Which is most likely true.

But if you ask an outsider, someone who was not involved in the creation of that original system, the answer would be different.

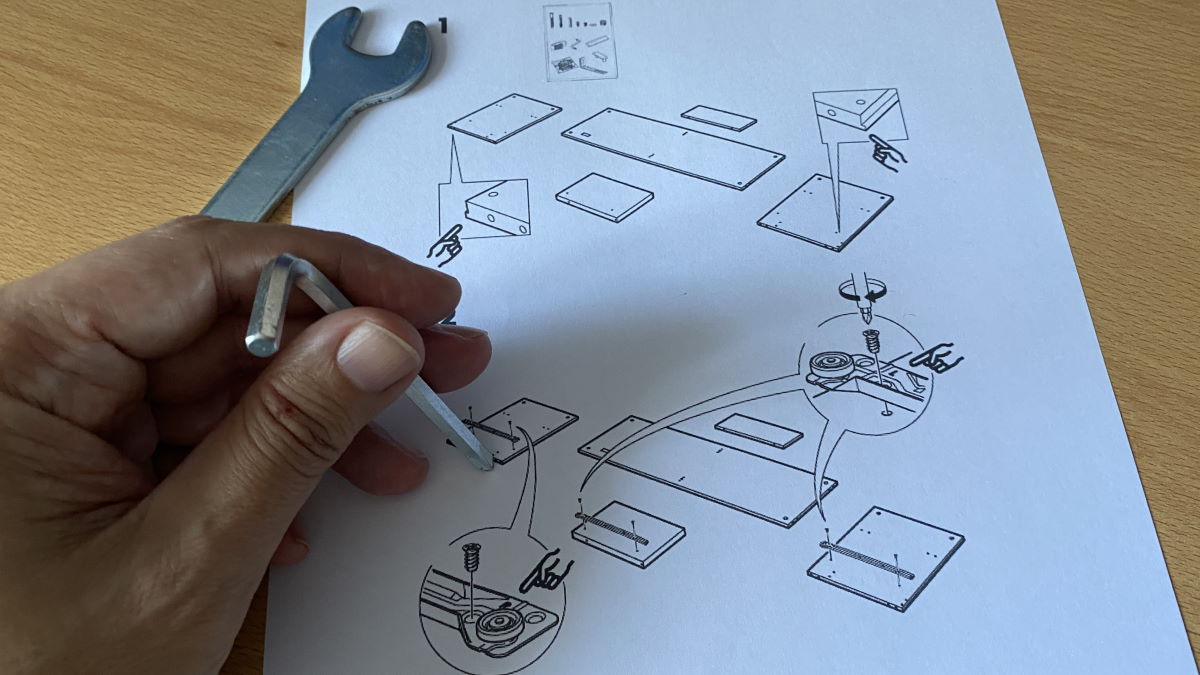

The short answer is what is called the IKEA effect.

That tendency we all have to give more value to what we have made ourselves.

Is that TV cabinet that we have assembled, like a jigsaw puzzle, using all Saturday afternoon better than the one that has been brought to our living room already perfectly assembled?

It is a very subjective thing.

And, going back to business-critical systems, this sometimes ends up translating into decisions that, depending on how you look at it, can be considered almost sabotage.

We’re going to put a team in place to develop a new system to replace the old one. But, while they develop it, we keep making changes and improvements to the old one so that the new one will never measure up.

When the high season approaches, emergencies arise that require that people working on the new development have to leave it temporarily (because, after all, it is not yet operational) to help with improvements to the old system (which is the one that is really being used).

We know that it’s been 10 years since anyone has used the functionality that was developed in the old one, but nobody dares to remove it, just in case they need it again in the future.

And so on, so many arguments.

This is not an isolated case.

There are many companies where replacing the current system with a potentially much better one is an almost impossible task.

And not only when it comes to in-house developments.

The same applies to purchased applications that have been there for 20 years and that the users have internalised so much that they feel it as their own.

The working system they have organised on the basis of that application is their own creation.

And they have their own IKEA effect.

Sometimes the only way to replace it is to change the people in charge of that system. When a new vision comes in, that’s when you question a lot of things.

Are you giving up opportunities by sticking to the old system?

Does it make sense to keep it that way?